To read the full research behind this op-ed, visit our 2024 Hatfield Prize page here.

At just 15, Carlos fled his home in Honduras to seek medical treatment for an eye condition, a better education, and safety from gang-related violence in his hometown. Carlos crossed the U.S. border alone and was immediately arrested and held at a Texas detention facility. Soon he was transferred to a Miami shelter care facility for unaccompanied children that was his home for the next two and a half months. After 82 days, Carlos was placed under the care of his “sponsor”— an aunt in New Jersey.

He was excited to leave the strange and crowded facility in Miami and finally see a family member, even though he had only met his aunt once when he was very young. Now he continues to await a court hearing that will determine whether his status as an asylum seeker will be confirmed. If confirmed, he will have legal status in the U.S. but if denied, he will be deported.

Carlos’ story is true and hardly unique. Hundreds of parents — often unable to afford to pay for their own journey – send their children to the U.S. border, reliant upon the protection and policies of the U.S. federal government and praying their children will eventually find a better life. Providing care to this extremely vulnerable population is enormously challenging and requires the partnership and coordination of the federal government, states, non-profit organizations, churches, and communities.

In 2023, the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) — the federal agency charged with the care of this population – received 118,938 unaccompanied children (UC) into their care. While the reasons for children and adolescents crossing the border alone are multiple and complex, the vulnerability of this population must supersede any political arguments related to immigration. For the past nine months — as a part of my research for the Center for Public Justice’s Hatfield Prize — I have been researching the nature of UC care, specifically exploring the roles that Pennsylvania and my home city of Pittsburgh can play in this network.

While the reasons for children and adolescents crossing the border alone are multiple and complex, the vulnerability of this population must supersede any political arguments related to immigration.

After speaking with UC policy experts and the directors of numerous Pittsburgh nonprofits, I have concluded that my city and state, and plausibly other cities and states located far from the border, have the untapped potential to expand their role in UC care, taking pressure off overextended border states. In fact, I conclude that Pittsburgh and other similar places — though geographically far from the border and therefore not those that come immediately to mind when discussing immigration — are hospitable and well-resourced places where increased UC care would likely flourish.

Thankfully, there is a strong historical precedent for cities like Pittsburgh that can offer more services to UC. In 1997, the passage of the Flores Settlement Agreement signified a major improvement in the care of UC by codifying requirements for ORR-contracted facilities including services related to UC’s physical, educational, and psychological needs. Under The Flores Settlement Agreement, ORR-contracted facilities must feed, shelter, clothe, educate, provide medical and mental health care, and work to expediently locate a familial sponsor or a stable foster home. These are places where UC live for approximately a month while trained social workers seek to place them with a sponsor.

However, there is currently only one ORR-contracted care shelter facility in Pittsburgh: Holy Family Institute. There are only two facilities in the entire state; the other one is near Philadelphia. Pittsburgh and similar cities could greatly enhance the overall UC network by empowering the existing network of social service providers to provide two types of care for unaccompanied minors. The first type of care would be additional ORR-contracted shelter care facilities.

The second type of care cities like Pittsburgh should support are foster homes where UC can be housed on a longer-term basis. Sometimes it is necessary to match a minor with a foster family when an acceptable sponsor is not located in the U.S. This may also happen if a child is classified as an unaccompanied refugee child who arrives legally from another country, but without a parent.

While encouraging local nonprofits to expand into UC care is a promising idea, some may wonder if Pittsburgh or other cities that might be further from the border would be the best places to expand UC care. My research actually found a vast nonprofit network in Pittsburgh that is effectively already assisting adult immigrants. While many of the organizations in this network do not officially exist for UC, their services are adjacent to those needed by UC. For example, many organizations have taught English, supported job placement, and provided pro bono legal assistance to immigrants for years.

In an interview I conducted with Monica Ruiz, Executive Director of Pittsburgh’s Casa San Jose, a Latino community center, I learned that many local nonprofits come into contact with UC and end up involved in their cases. Ruiz told me, “We can’t do the work ourselves. Latino Community Center [Pittsburgh’s other community center for Latinx] works with community [public] education where Casa San Jose does not.” Pittsburgh has many well-established foster care agencies including families that would likely have interest in fostering UC specifically.

Taking care of unaccompanied children in non-border states that already have the capacity to expand their resources to UC could mean that these children are given the opportunity to better their lives through a good education, better healthcare, safer neighborhoods, and a community of support. With these resources, UC can be given the chance to thrive and give back by participating in the economy and entering the workforce. Without the support of local communities, these opportunities are not possible for a UC and could lead to instability in communities.

Fortunately, Pittsburgh is a northern city that is receptive to immigrants and can make UC flourishing a reality. In an article by The Washington Post, Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey said, “We are not here to reject any immigration. As a matter of fact, we want to make this the most safe, welcoming, thriving place in America, and you can’t do that without immigration.” With the support of the city government, local nonprofits in the city have the opportunity to implement UC programs without fear of backlash.

Moving toward this reality starts with local nonprofits with the capacity to apply for ORR contracts, both in the areas of providing shelter care and/or foster homes. The ORR has three paths organizations can take to become contracted. Path one is for facilities that want to directly care for UC. Path two involves subsequent services or the providing of services for a temporary amount of time. Finally, path three is for those who want to give resources to UC without actually caring for them. These applications and contracting timelines depend on the path the agency is applying for and their eligibility.

The call to expand UC care also extends to churches, who have the unique ability to support local nonprofits by providing donations, volunteers, and spiritual role models for UC.

We see a trend in care facilities for UC being affiliated with religion. For instance, 40% of ORR-contracted facilities across the U.S. are faith-based. This significant finding is consistent with what we heard from the religious organizations we interviewed about the deep sense of calling they have to serve vulnerable populations like unaccompanied minors.

As Christina Staats, a mobilizer for Bibles, Badges, and Business at the National Immigration Forum, told us in an interview, “If we are going to have children in our system, we have to [do] due diligence.” How can we do this?

While fostering can be difficult at times, providing a safe, loving, family-like environment for a UC helps contribute to their well-being.

Individuals interested in going beyond public education can aid existing organizations dedicated to helping UC. Volunteering at a Latino community center, donating to a reputable non-profit that work with UC, or getting involved in a local church ministry dedicated to helping UC are great areas to start. Opening one’s home to foster a UC is another way to help UC directly. Fostering UC gives the ORR more space to send UC to a proper and safe home. While fostering can be difficult at times, providing a safe, loving, family-like environment for a UC helps contribute to their well-being.

With a growing number of children entering the country unaccompanied by an adult, it is essential to spread out care locations to other parts of the U.S. rather than border states. Like Pittsburgh, many cities across the U.S. have the potential to provide a robust set of services for unaccompanied children, helping children just like Carlos, who was able to graduate high school and go on to work in manufacturing thanks to the support he received.

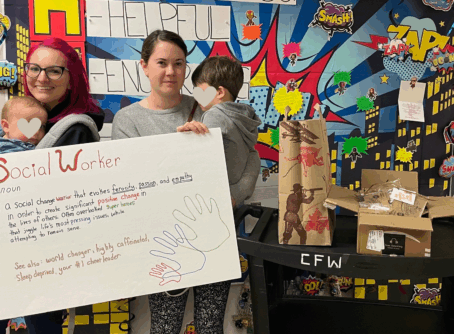

Megan Brock studies Social Work at Grove City College. She is from the Pittsburgh area and is passionate about working with children and teens in her community who suffer from trauma. Megan hopes to learn about the problems faced by youth in her community and help improve the lives of children through trauma informed practice. Megan aspires to work with youth who struggle with behavior problems and to empower them toward future flourishing.

Lisa Hosack serves as an Associate Professor of Social Work and the Calderwood Assistant Dean at Grove City College in the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania. She teaches and researches in the areas of international child welfare, social welfare policy, and clinical social work. Dr. Hosack is married with three grown daughters and an accommodating cat named Felix.