Young adults are one of the groups that are hit hard by our nation’s criminal justice system — especially those ages 18 to 25. Justice-involved members of this age group begin their adult lives estranged from community, whether in prison or haunted by its consequences outside, such as limited societal rights, disenfranchisement, and excessive shame and stigma. Unfortunately, this uniquely situated age group is often invisible in policymaking because they are not juveniles. Yet, they are in a vulnerable developmental period that should differentiate their treatment from older adult offenders. The Annie E. Casey Foundation, while committed to children, also recognizes the uniquely vulnerable time between the ages of 14-24 as well as the great hope for transformation and development in this life stage. In an effort to elevate youth and set them up for success, they have initiated a Thrive by 25 focus at the Foundation that seeks to find ways to strengthen and build communities starting with children and youth and seeing them through to adulthood.

Injustice occurs when our criminal justice system inhibits young adults’ capacity to grow and live crime-free lives as valued members of the community once their sentences are up. The Center for Public Justice’s Guideline on Security and Defense states, “Government’s responsibility for domestic security and retributive justice is institutionalized in the form of police forces and court systems, which enforce and adjudicate the law against lawbreakers and ensure restitution for victims. As much as possible, the police and the courts should aim to reconcile victim and offender and to restore a just order.” Christians in particular should respond to the injustice of the lack of reconciliation in the justice system by equipping justice-involved young adults to flourish in the way God desires for all his people.

In order to care for young adults who are at risk of entrapment in the criminal justice system, we must start from the ground up. One direct risk factor for perpetual entanglement with the justice system is detachment from the community. If young adults cannot find a social network to support them—both interpersonally and through connecting them with needed resources—they will lack the guidance and tools to thrive.

Why start here? The Annie E. Casey Foundation outlines eight core principles we must implement to break the cycle of the criminal justice system. All of them revolve around forming a more caring and compassionate approach to civil society. In their words, “Building a world where all young people are able to thrive and grow into responsible adults requires us to respond more effectively when young people experience harm and when they offend. Instead of using concrete cells and barbed wire to intimidate and control young people in prison-like settings, we would provide young people with steady relationships with caring adults.” This certainly extends to those in the young adult age group, who are automatically disadvantaged by spending a vulnerable period of valuable growth and development behind bars. By heeding the research of the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Christians commit to being present for these developing, emerging adults both while they are incarcerated and upon their release, encouraging and facilitating connections for them with various institutions.

For young adults like me, enrolled in college and part of organizations such as Arcadia Christian Fellowship (ACF), we have safety nets when things go wrong, but only if we utilize them. As a member of ACF, I spoke to Ben Thompson, Campus Minister/Off-Campus Religious Adviser with the Coalition for Christian Outreach (CCO) and leader of ACF, about connection and community on college campuses — or rather, the lost art of community as a social safety net.

Thompson said that “anytime anything bad happens to college students, 90% of them retreat from community rather than use community as a support system for hard times.”

If current college students, some involved in the justice system and some not — have a hard time accessing community safety nets and the communal support they need to start adult life well — how much more difficult is it for emerging adults to access the resources and assistance they need to avoid the justice system, or to reintegrate back into their communities well, when they return?

“I think most students don’t know what a healthy community looks like and so [they] don’t know how to envision it,” Thompson added.

As a Christian and emerging adult on a college campus, I see a disconnect between resources and needs that leads me to ask: why do many young college students not utilize the campus-wide and community resources that they pay for as part of their tuition or have access to by virtue of living in that community? Beyond the college campus, why do young people in America feel unsupported by community members and organizations despite some perceptions that there are many public services and goods provided by the government?

Arguably, a big part of the answer is that community spaces and resources have not actually been accessible or inclusive throughout history. For many young adults moving through the revolving doors of detention centers and prisons, they cannot discover the available resources. In turn, when these resources fail, people are forced to look to themselves.

Thompson noted that many emerging adults “are working three or more jobs on top of studying full-time. The fact that students need (or think they need) to work so much in order to function really hinders their ability to plug into the community on campus.” It is also important to recognize that youth who are not in college may face an even worse drought of community-based resources when it comes to navigating the justice system. Working youth may be at a point where they have to choose between going to a church/community meeting or not—a cycle of exhaustion can easily lead one to stay home, and depending on where “home” is, this is where contact with the criminal justice system could start.

Thus, we must make church campuses and other community spaces feel more like a “home” as well. This means that these must be places where people do not feel they have to dress up, play a part, or hide some of themselves in order to show up: we must make them accessible places of inherent belonging.

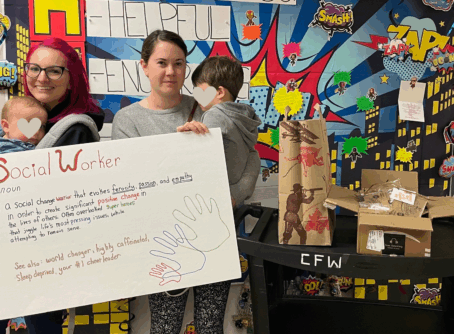

Thompson says that ACF is “a place for students to go when they are going through hard times and need support. Having a group of people to support you when bad things happen is really important for your mental, emotional, and spiritual health.” ACF recognizes the range of needs in emerging adults and therefore serves as a model for the holistic support we must offer young adults who are reintegrating from the justice system into society. The services of ACF are oriented toward spiritual and emotional needs such as meetings where community speakers are invited to share testimonies, free retreats, providing prayer partners, as well as physical needs, such as connections to community resources such as food banks.

We must build places of belonging if we want to equip justice-involved young adults to reintegrate into our communities well. Additionally, larger public institutions must be centered around care and equity. These places, particularly the justice system, are inherently meant for people to show up with their problems. In return, those in need should be able to find compassion, education, empathy, respect, resources, trust, and action to move forward. Being rooted in community creates an unspoken social contract, with obligations to others and gives agency to those who suffer when systems malfunction. If more institutions had initiatives which sought to strengthen a sense of community, perhaps young people and their needs would become more visible to society, and society’s resources would become more visible to young people.

While community includes accountability for decisions, a criminal sentence should not be a death sentence. We as a civil society must make it possible for those who enter the system at a young age to forge a new path forward on the other side of it. Although this is difficult work, the apostle Paul reminds us to”carry each other’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ” (Gal. 6:2). We are not meant to live in isolation or shame. We need compassion, mercy, and care to live restored and restoring lives. True justice can only occur in our communities where this is our standard.

Nicole Burgon is a first-time writer with CPJ. She is a college student at Arcadia University in Glenside, PA. She is on Instagram at @nicole_burgon.